Shakespeare Quote

"As man can breathe and eye can see, so long lives this and gives life to thee."

New Video Released June 6, 2021

Virgil Elliott's long-awaited video, The Principles of Visual Reality is now available from Liliedahl Publishing.

Buy via this link:LiliArtVideo.com/elliott-release

Interview on The Artful Painter Podcast

Virgil Elliott - The Pursuit of Quality

www.carlolson.tv/artful-painter/virgil-elliott-the-pursuit-of-quality-15

Notable Women Artists of the Past: Artemisia Gentileschi

[This article was originally published in The Portrait Signature, 2000, Volume 4]

Prior to the Twentieth Century there were precious few women who achieved any appreciable degree of recognition as artists. Those who did so deserve to be acknowledged for having persevered in the face of social prejudices, taboos and prohibitions that male artists did not have to overcome in the development and marketing of their own talents, and which women artists of today likewise have not had to endure to such a degree, at least in the field of art. The church was a powerful and dominant force in Europe, and considered it inappropriate for women to study the nude male figure, or to depict it in drawings or paintings. This was but one of many handicaps imposed on women wishing to pursue art as a vocation in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In Renaissance and Baroque Italy only the daughters of artists and girls of noble birth were given training as artists. Noble women were expected to be well versed in all aspects of culture, including drawing and painting, and thus were taught by artists hired by their families to tutor them in these disciplines. There were, however, restrictions on what subjects were deemed appropriate for them and what were not, as it was more important that they be proper ladies than great artists, in the eyes of society. Consequently, the training most of them received was not as complete as it was for male students and apprentices. Of the women who were trained in art, most of them did not go on to pursue careers in that field, instead abandoning it, for all practical purposes, when they married and had children. Their artistic endeavors thereafter were done more as a hobby than a vocation, in most cases, with a few notable exceptions.

Although few Masters would accept female students in those days, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) was privileged, as the daughter of the painter Orazio Gentileschi, to study under him while still a child, working in his studio as an apprentice from age seven or so, and subsequently to study with Guido Reni, according to one account. As her father was a contemporary of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio at a time when both lived and were active in Rome, it is highly likely that Artemisia would have known him while she was very young and in her student stage, and most certainly would have seen his paintings. Her work does show a strong Caravaggio influence. A scandalous figure himself, Caravaggio defied conventional tastes and attitudes in his painting and his life, shocking the public with depictions of holy figures more naturalistic than the idealized images then in vogue, and by outrageous behavior in his personal life (including killing a man in a fight). Perhaps the young Artemisia might have been impressed by this as well as by the powerful visual impact of chiaroscuro in his works. She was to exhibit her own fierce determination in defiance of the prevailing attitudes of society at the time. Despite the many prejudices against women working in what was generally regarded as a man’s field, Artemisia, solely through the quality of her work, gained a reputation as a portraitist and history painter surpassing that of her father, and established herself as a successful artist in her own right.

We may regard the recent movie, “Artemisia” as fiction, though there were elements of truth in it here and there. Whereas the movie treated her association with Agostino Tassi as a love affair, the truth is well documented in trial records as being entirely different. While Artemisia was still a teenager, her father asked Tassi, a landscape and seascape painter with whom he had been collaborating, to teach her perspective, as he was known as an expert in that particular aspect of art. At one of these lessons Tassi forced himself on Artemisia, who cut him with a knife in her fight to resist. Contrary to the movie story, there was no love affair between them, though Tassi did offer to marry her after forcibly deflowering her. His sincerity might be seen as open to doubt, in light of the fact that he did not follow through on his promise. Artemisia’s predicament, as a non-virgin, compelled her to look at this possibility as her only hope of maintaining a respectable reputation in the eyes of the society in which she lived. Tassi, however, reneged on his agreement, and Orazio filed suit against Tassi for the rape of his teenage daughter when he found out about it. A trial ensued, and throughout the proceedings, which included the physical torture of Artemisia to ascertain her truthfulness, she continued to maintain that it had not been consensual, as Tassi had contended. In addition to the torture, a measure commonly employed in trials in those days, she was subjected to a humiliating ordeal in the form of a vaginal examination to establish that she had been a virgin prior to the attack, to counter Tassi’s charges that she had been with many men before him. It soon came to light that he had been sued for rape before, had impregnated his wife’s sister, had arranged to have his wife murdered, and had obtained this same wife in the first place by raping her and then proposing marriage, as he had with Artemisia. The trial officially cleared up any questions regarding Artemisia’s virtue prior to the rape, but nonetheless left her marked for life in a number of ways. Shortly after the trial, Artemisia married the Florentine painter Pietro Antonio di Vincenzo Stiattesi, who had testified in her favor at the trial, in contradiction to Tassi’s assertion that Artemisia had been promiscuous, and the couple moved to Florence. There has been much speculation on the effects of the ordeal on her psyche and her motivations for painting the Old Testament Biblical story of Judith beheading Holofernes more than once, with good reason to suppose a connection.

After moving to Florence, Artemisia gained a number of lucrative commissions, and became an official member of the Academie del Disegno in 1616. She painted several versions of Judith Slaying Holofernes, a theme also painted by Caravaggio, and other paintings depicting historic and Biblical stories with female heroes, some of them executed while living in Florence. It is known that she met Anthony Van Dyck and Velasquez when they were in Italy, on equal ground as contemporaries. She went to England around 1638, or perhaps earlier, residing at the court of King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria, and painted there for two or three years, including a collaboration with her father on a large commission for the Queen’s House at Greenwich.

Thirty-four paintings by Artemisia are known to exist today, though she undoubtedly painted many more, some of which may not have survived, and some of which could possibly be attributed to other artists.

Artemisia Gentileschi overcame all the difficulties she encountered, and established herself as a well-respected artist quite independently of her father and her other teachers, with a successful career that lasted until the end of her life at age 60.

While we may certainly lament the extreme unfairness of the terrible treatment Artemisia had received as a teenage girl, the least of which were the restrictions on the teaching of art to female students, it is highly likely that this episode, and its effect on her, is what gave her work its extreme emotional impact. The emotional content is precisely what makes the difference between a competently painted picture by a well-trained painter, and a masterpiece. The best artists have always, and will always, put something of their own psyche, their own personal intensity, into their work, and it is that quality, strongly expressed, which connects with the sensibilities of the viewer and registers its impression indelibly and unmistakably upon them. These experiences, both positive and negative, serve to bring out that intensity and give great artists their unique identity, and their work its power. Thus the most trying ordeals, and the effects these trials and struggles will inevitably have on the artist, can be the genesis of something positive, and perhaps something great, when channeled into art.

Read more about Artemisia Gentileschi in Artemisia Gentileschi and the Authority of Art, by R. Ward Bissell, 1998, Penn State University Press

Podcast interview: Living Master Artist Virgil Elliott on Art from the Renaissance to the Present

Traci L. Slatton interviews Virgil on painting, drawing, music and teaching. Go to www.blogtalkradio.com/independentartiststhinkers/2015/10/01/living-master-artist-virgil-elliott-on-art-from-the-renaissance-to-the-present to listen to or download the one hour interview.

Virgil Elliott In An Alla Prima Portrait Webinar

Watch and listen as Virgil Elliott paints a portrait from life. For more information and preview visit www.juskathryn.com/blog/virgil-elliott-promo-ii

Update on Oil Painting Mediums

(Published in The Classical Realism Journal, Volume VIII, Issue 1.)

One of the most frequently discussed topics among oil painters is oil painting mediums. There exists a wide diversity of opinion and preferences on the subject, both in books and from artist to artist, with certain mediums enjoying almost cult-like advocacy. Much information has been published on the subject, some written by persuasive authors, many of whom disagree with one another on many points, resulting in a great deal of confusion over which ingredients are best for a given painting style. As in most things, the issue is not as simple as it might seem. It must go beyond focusing on the mediums alone, and begin with the reasons painters feel they need them in the first place.

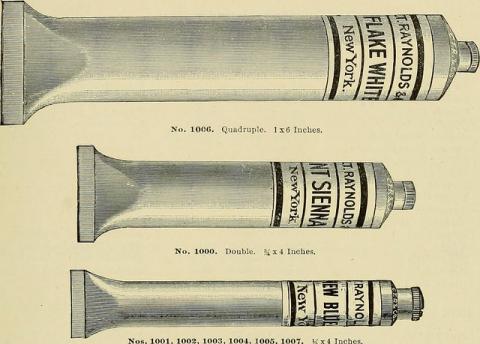

Some commercially available oil paints, as they come from the tube, are of a stiff consistency that does not facilitate the utmost in control, and thus require the addition of something to improve their brushing qualities. Enter painting mediums. It is important to note that in the days of the Old Masters, the paints were ground in the artists' studios, by the artists and/or their apprentices, in all likelihood to the desired consistency for optimum control under the brush. In such an instance, there would be little or no need to add any medium at all. This hypothesis seems to be borne out by scientific testing conducted by the National Gallery,in London, on many of the paintings in their possession. The preponderance of the 16th and 17th century paintings tested showed no detectable resin content in the paint layers, to the surprise and disbelief of so many who had read 19th and 20th century accounts alleging that specific artists of the earlier times used mediums containing natural resins like mastic, copal or amber. What was found, in most cases, was pigment bound in linseed oil, and in some cases, walnut oil. The indication is that the addition of resin varnishes to oil paints as a common practice dates back to perhaps the mid-1700s, and no farther, with certain individual exceptions. Of course there are many unanswered questions, and the possibility remains,at least theoretically, that the testing methods used were simply unable to detect the resins that might actually have been there. Thus it is not necessarily a closed issue, at least in the minds of those mistrustful of science. But if the current prevailing opinion in the conservation science community is correct, as the best evidence strongly suggests,there may well be a correlation between the widespread use of resinous mediums and the introduction of pre-prepared oil paints on the scene.

To artists making their own paint, the only concern would have been the quality of the paint, but to those in business to make a profit selling paint, the temptation to add less expensive ingredients to keep production costs down was very strong. It is known that many adulterants and fillers were added to paints sold ready-made by artists' color men, and this undoubtedly affected the brushing qualities of the paints in question. The need for mediums to improve the consistency of the paints seems to have grown from this. In modern times, manufacturers add aluminum stearate, a soap, to mitigate the tendency for oil and pigment to separate in the tubes as the paints sit on store shelves or in artists' paint boxes. Aluminum stearate changes the oil from a fluid to a more colloidal consistency, and changes the way the paint handles. However, some manufacturers exercise greater restraint in the use of such substances than others, and artists have choices. With this in mind, the painter of today can get by with less medium simply by choosing less stiff paints to begin with, or by grinding his or her own, as was done in the days of Rembrandt and earlier. There are a number of quality paints currently on the market that exhibit a fluid consistency as they come from the tube, and require little or nothing to be added to them in order to be controllable. Should they require a bit more softening, a drop of linseed or walnut oil may be all that is needed.

From a structural standpoint, the strongest paint layer is one with the optimum ratio of binder to pigment. The best commercially available oil paints are already very close to this ratio. Adding too much of any medium is likely to produce weak spots in the resulting paint film for lack of sufficient solid matter, just as a wall made with poorly fitting stones and too much mortar will be weaker than one in which the stones fit more closely together and a minimum of mortar is used.

Natural resins were long thought to impart desirable properties to oil paint films, but this belief may well be in error, at least as far as permanence is concerned, as each introduces its defects into the paints to which it is added. Discoloring and embrittlement over time are chief among these defects, which are well documented in art conservation circles.The prevailing opinion there, based on the best information to date, is that the paintings composed of simple combinations of linseed oil and pigment are more durable and less problematic over the centuries than those containing significant amounts of any of the natural resins. The works of Rembrandt and others seem to bear this out. Of course, in the world of science, there is always the possibility that new information will come to light that will warrant the revising of opinions. Research is ongoing.

References:

National Gallery Technical Bulletin, Volumes 15 and 17, National Gallery, London Rembrandt: The Painter at Work, by Ernst van de Wetering, published by Amsterdam University Press Art in the Making: Rembrandt, by David Bomford, Christopher Brown, and Ashok Roy, with contributions from Jo Kirby and Raymond White, published by the National Gallery, London On Picture Varnishes and Their Solvents, by Robert L. Feller, Nathan Stolow, and Elizabeth H. Jones, published by the National Gallery of Art,Washington, D.C.

©Virgil Elliott, 2002